You know Angels Flight. But what about L.A.’s other funicular railways?

- Share via

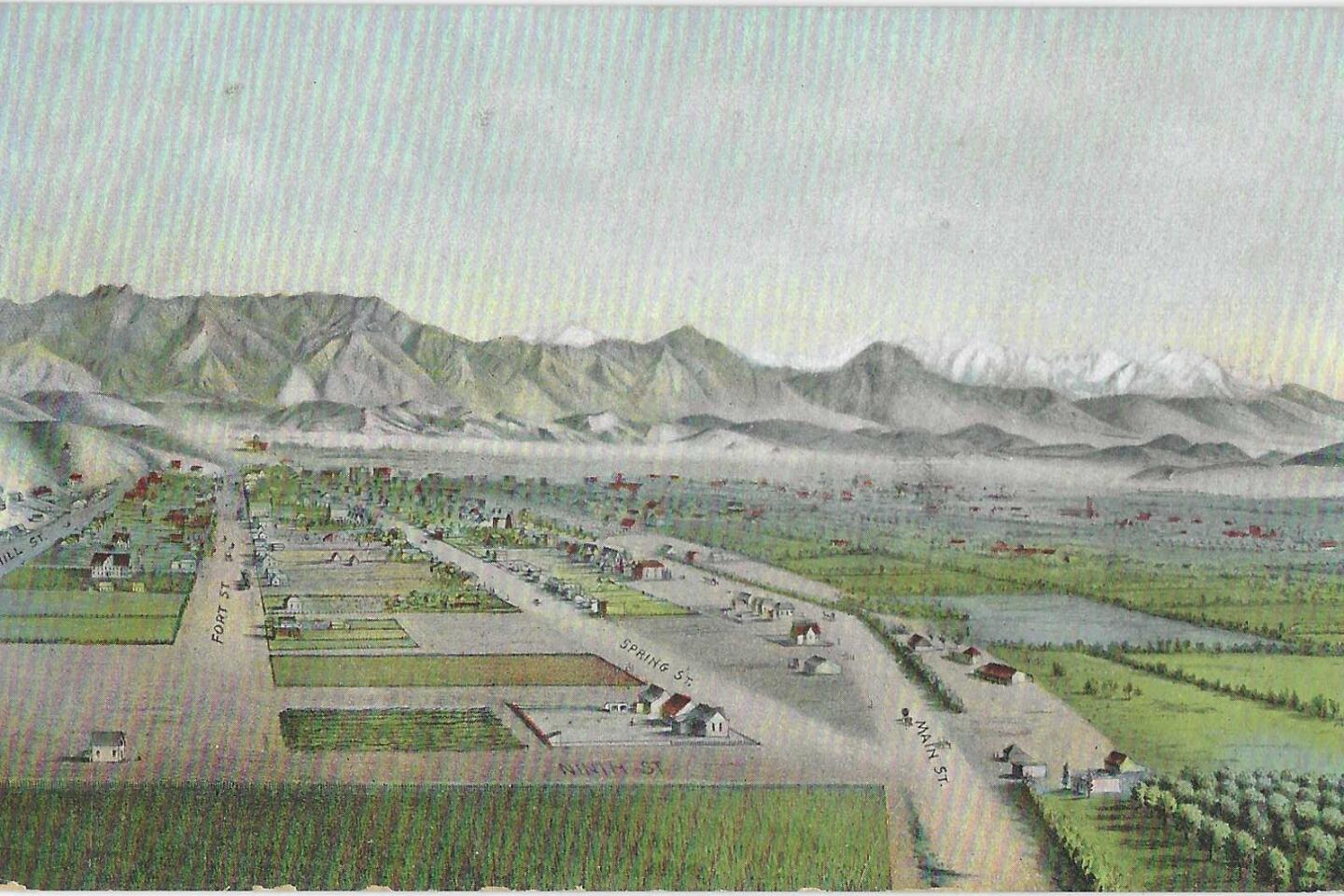

You may just be getting home from one hideous slog of a commute, so I don’t need to tell you that Los Angeles is one humongous city. It’s 469 square miles, the size of one and a half New Yorks.

If you were to take a rolling pin to L.A., the hills and canyons and mountains would flatten out into maybe another hundred square miles. The Hollywood sign hillside, the hilltop cup of Dodger Stadium, the knee-skinning slopes of Griffith Park — people who see L.A. for the first time marvel at the flatness of its flats, the rumpled reaches of its hills and mountains.

Look at yourself in the mirror, L.A.: You’re like a surfer’s dream waves, preserved in bedrock. The soft, ski-mogul hills of downtown and Pico-Union and Mid-City; the oscillations of El Sereno and Eagle Rock and Baldwin Hills, Silver Lake and Echo Park, Boyle and Montecito and Lincoln Heights, the San Pedro cliffs; the raggedy-jaggedy Santa Monica Mountains and foothills; and up in altitudinous Sunland-Tujunga, the peak of Mt. Lukens, a disappointing 200-ish feet short of being a mile high — all within the city limits.

They’re beautiful now. They were beautiful — and daunting — when Yankee Angelenos first laid eyes on them. How to navigate them? Over? Or around? Horse or wagon or shanks’ mare?

These were frustrating vistas for real estate agents eyeballing those charming hillsides and canyons with cartoon dollar signs in their eyes.

Theirs was the same problem that the tycoon Henry Huntington solved by building the Red Car system, his vast Pacific Electric railway, not so much to provide a public service as to transport buyers to the land he wanted to sell them.

Explaining L.A. With Patt Morrison

Los Angeles is a complex place. In this weekly feature, Patt Morrison is explaining how it works, its history and its culture.

But this was a vertical sales job, and funiculars were one solution to the first-mile/last-mile commuter conundrum that persists to this day.

That’s how L.A. came to have — and also to plan but never build — some “incline railways” of the kind you still see in Pittsburgh, in Europe and once again in the restored and re-restored Angels Flight railway in downtown L.A.

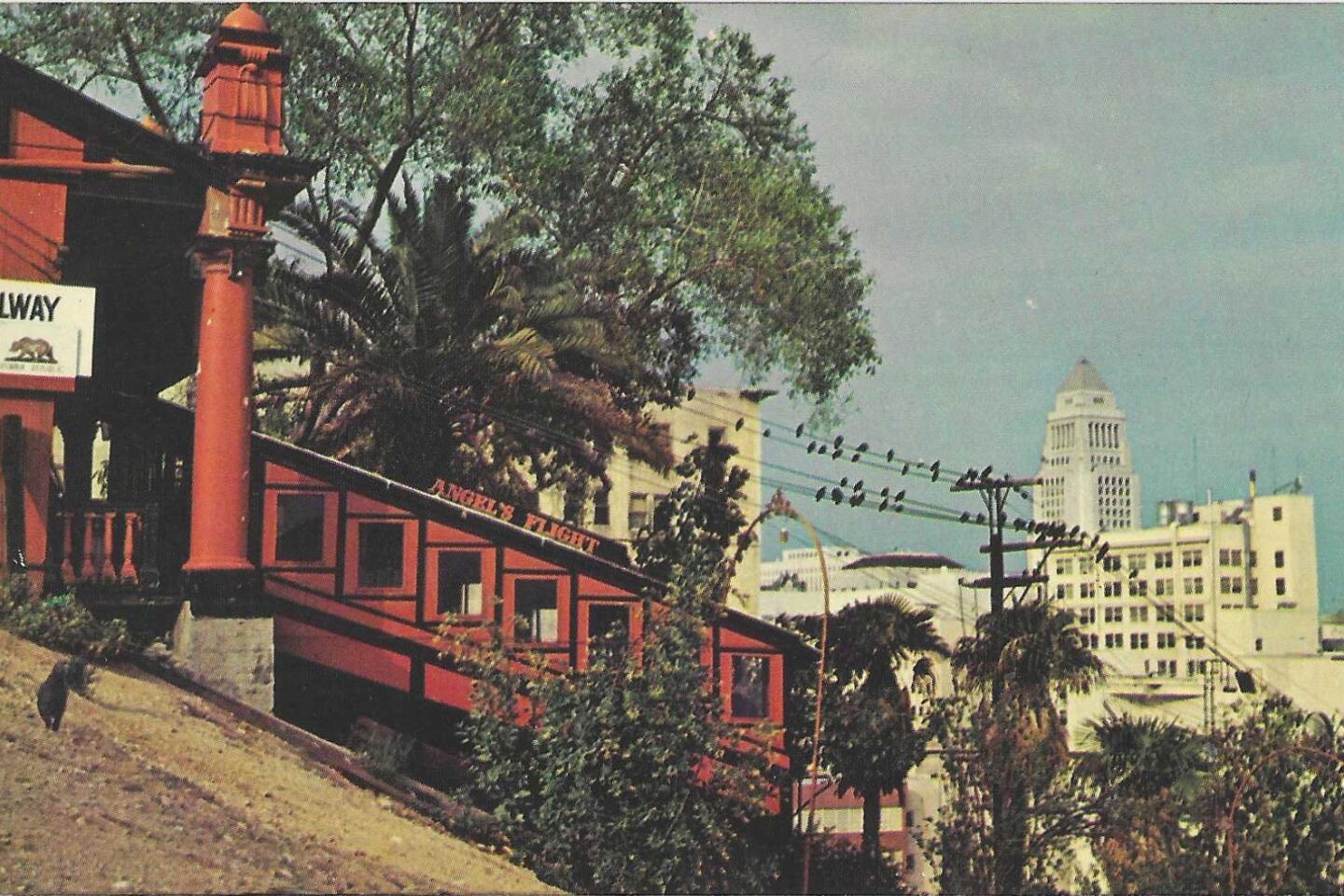

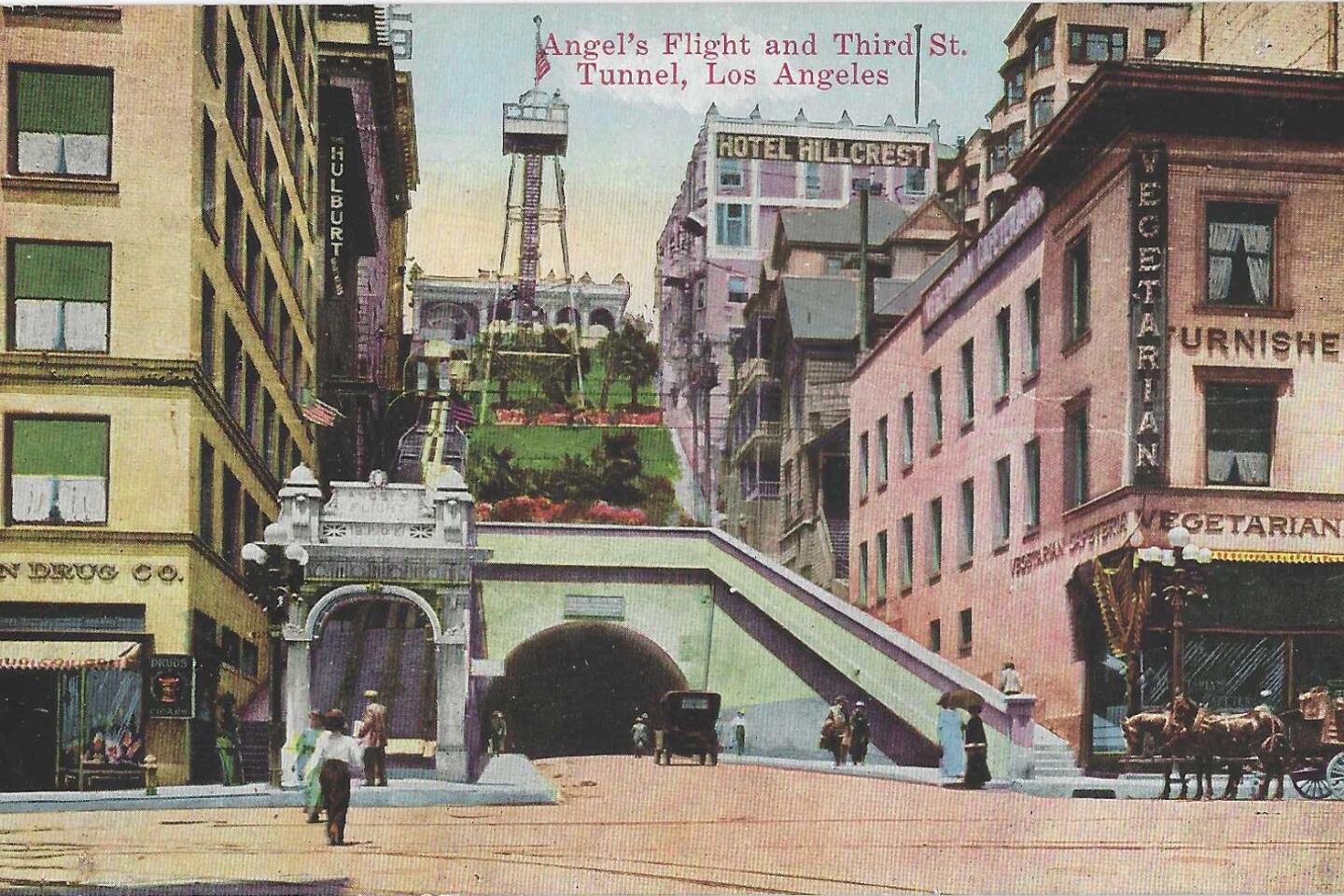

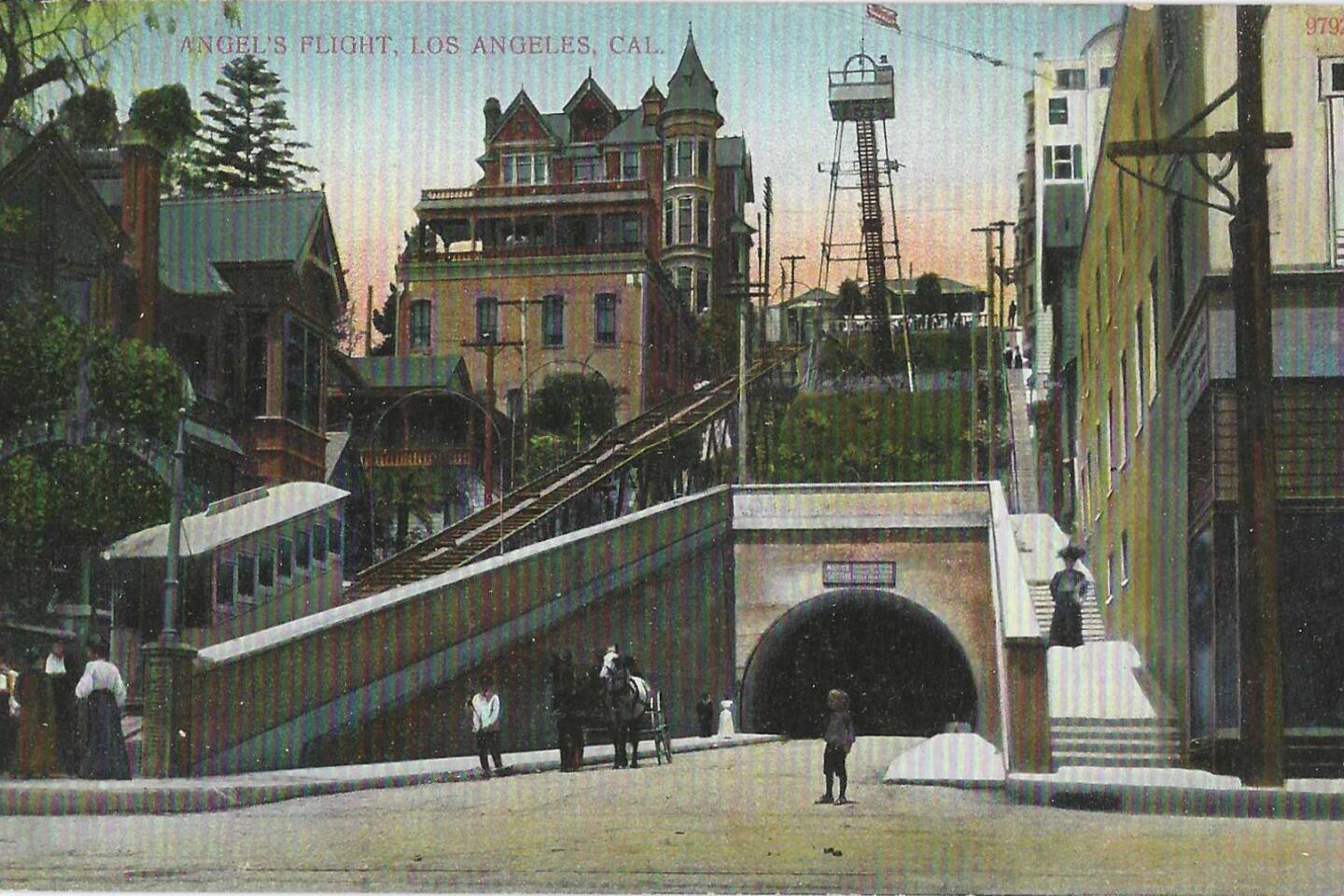

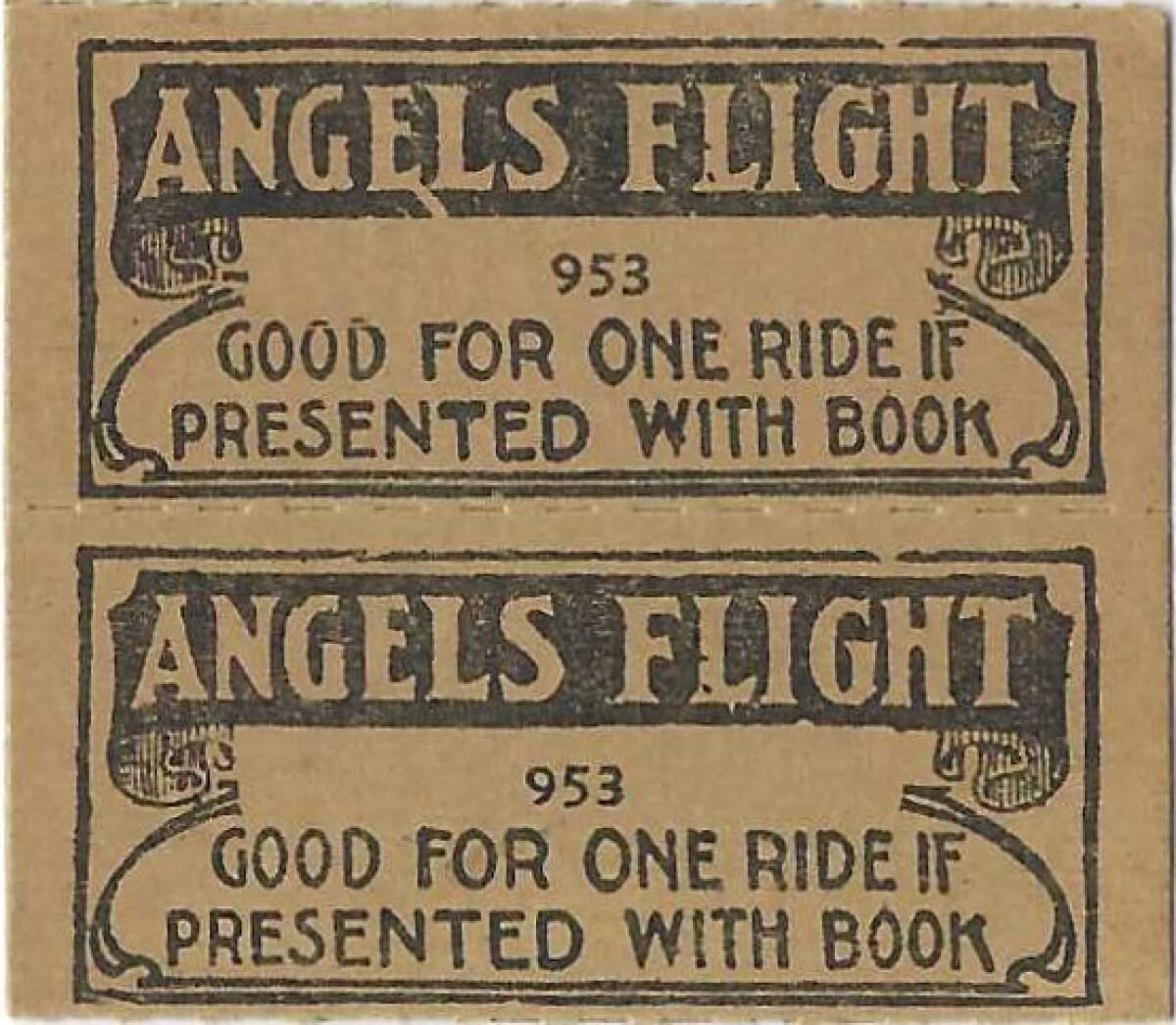

Angels Flight opened on New Year’s Eve 1901, the handiwork of Col. James Ward Eddy, a railroad man and an Illinois lawyer pal of Abraham Lincoln. You wouldn’t know it now, when the hilltop spine of downtown L.A. is the habitat of museums and performance halls. But before the vapid “urban redevelopment” of the 1960s and ’70s decapitated the top of L.A.’s Bunker Hill as neatly as slicing off the top of a soft-boiled egg, there was a whole neighborhood up there.

In fact, it was once the richest and fanciest neighborhood in town. Its lofty isolation inspired Eddy to build the counterweight cable-car system that sent two little wooden cars up and down “like a robber baron’s extravagant dumbwaiter,” wrote Jim Dawson in his book about Angels Flight.

It carried brides to their weddings in houses that looked like wedding cakes themselves. It carried mourners to funerals, and servants and masters to their daily errands. The cars were, briefly, as creamy white as angelic wings, and were named Sinai and Olivet after hills in the Holy Land. Later they were painted a sunset-orange color and edged in black. More on Angels Flight’s saga presently.

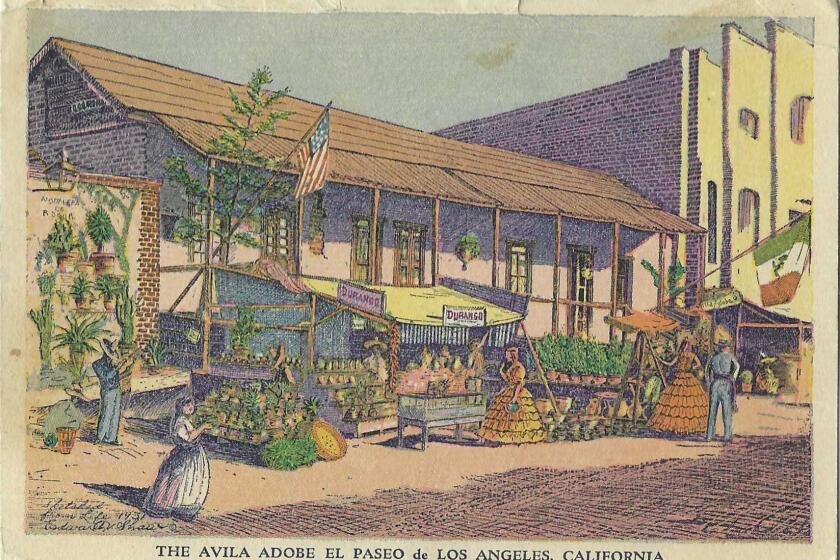

In the 1880s, L.A. already had some flatland electric railway cable cars. One system ran from the old plaza near Olvera Street all the way to an orange grove on West Adams Boulevard. Most of these systems foundered, and Huntington swept them up and built them into his Pacific Electric system.

But Eddy’s cleverly counterbalanced cars were a match for L.A.’s vertiginous hillsides. Three years after Angels Flight’s debut, the less picturesque Court Flight started ferrying court workers, from judges to janitors, up and down the far steeper hill between the court buildings down on Broadway and the neighborhood and parking lots above it. Its builder, owner and operator, Sam Vandegrift, never once, in the 28 years he ran Court Flight, took a day off for a ball game or a movie or any other amusement — unless you count those three days for his wedding and honeymoon.

After Vandegrift died, no similarly devoted soul could be found to run the thing, and during World War II, his widow officially abandoned Court Flight. A few months later, a carelessly flicked cigarette set the derelict tracks on fire, and it was case closed for Court Flight.

Native American settlements were first, and then the rancho system -- Spanish then Mexican land grants throughout California -- were built atop and near those settlements and still shape our geography and place names.

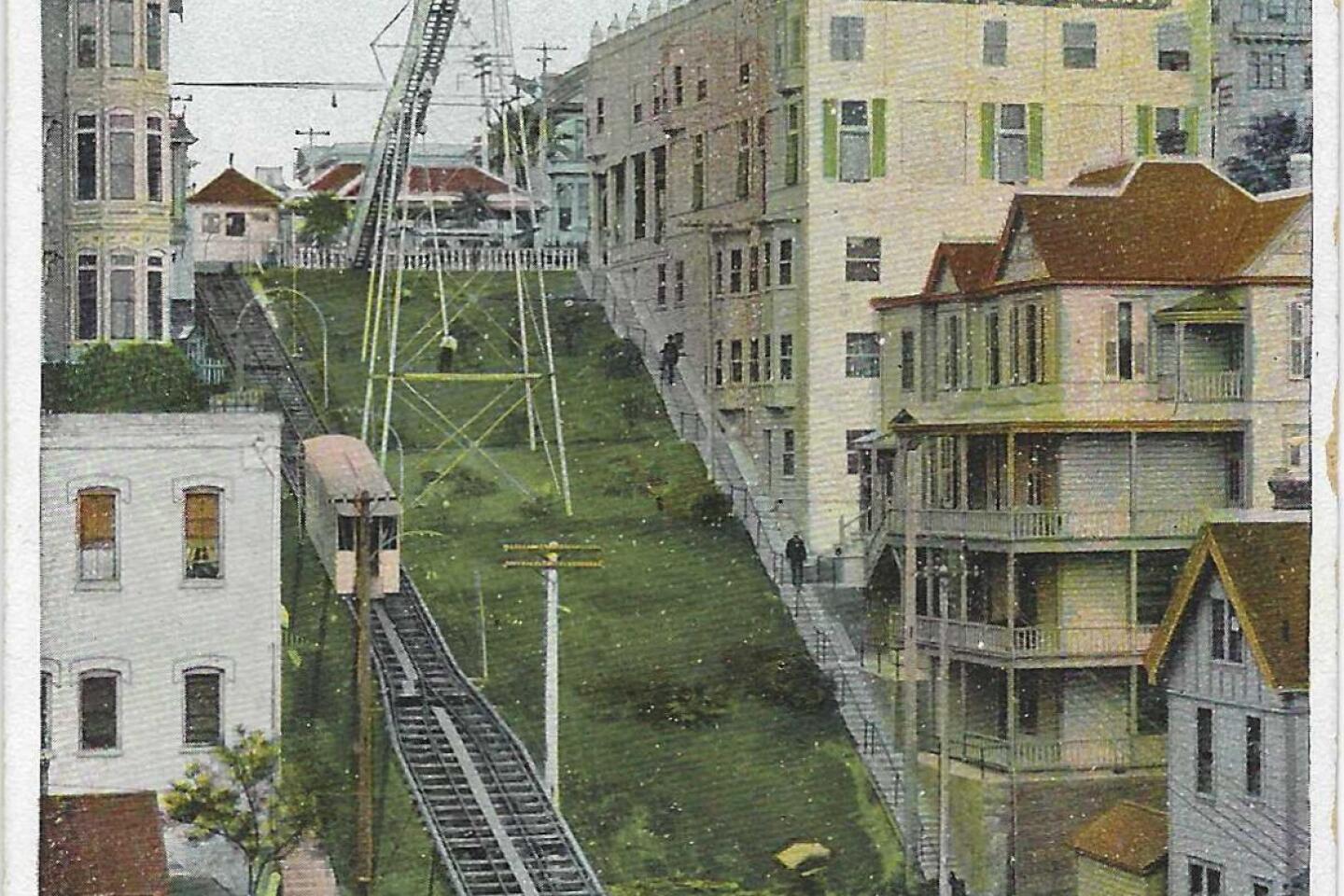

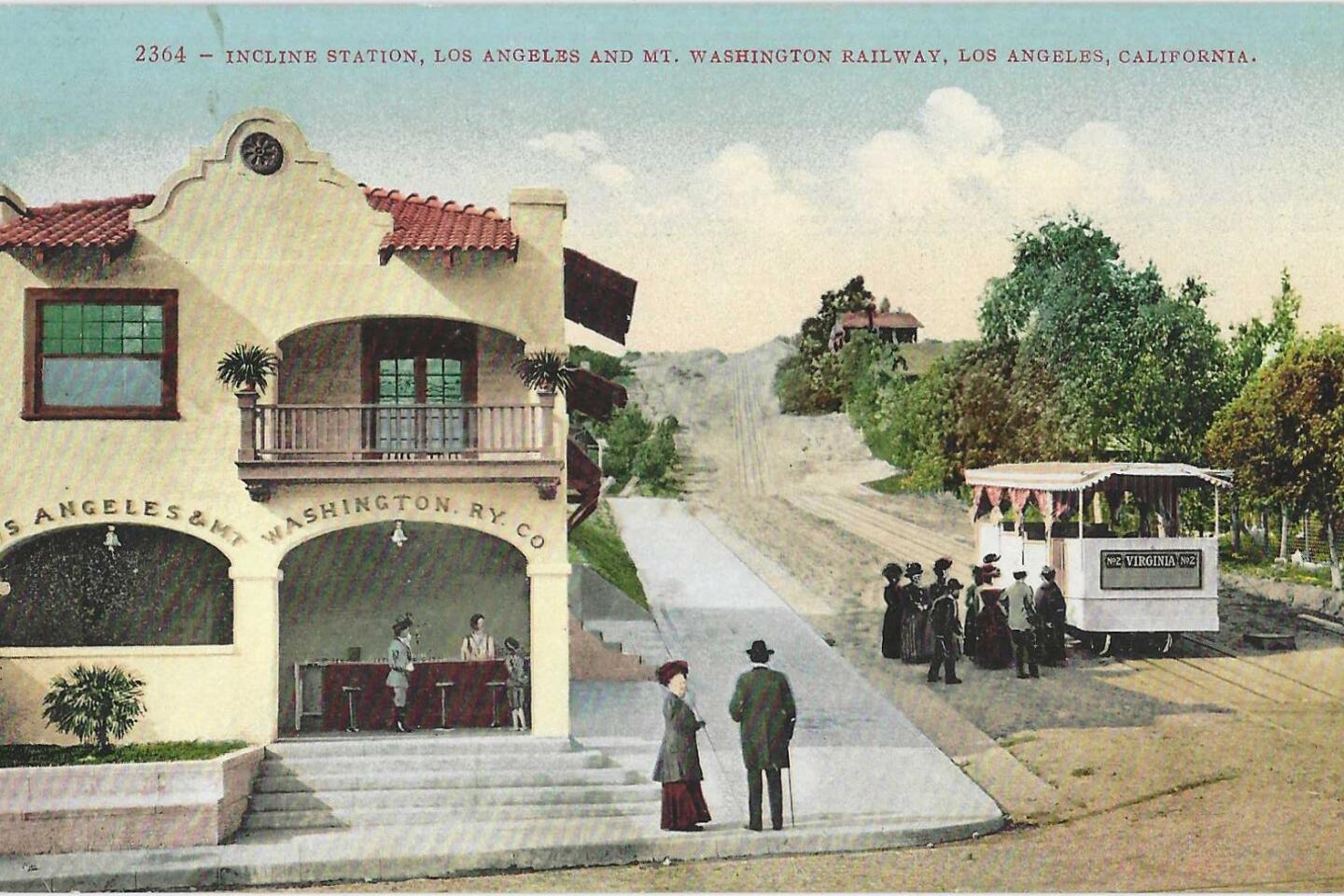

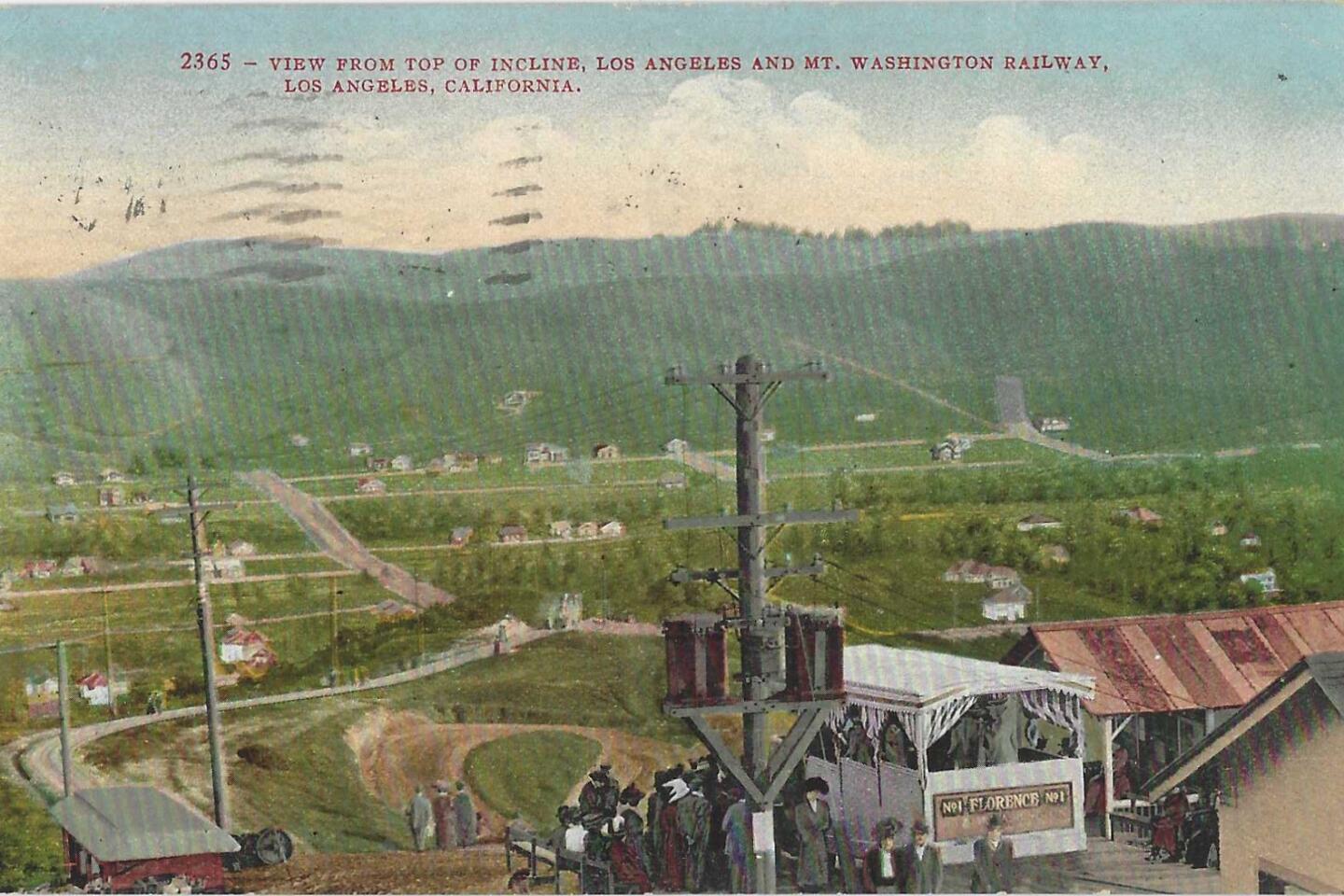

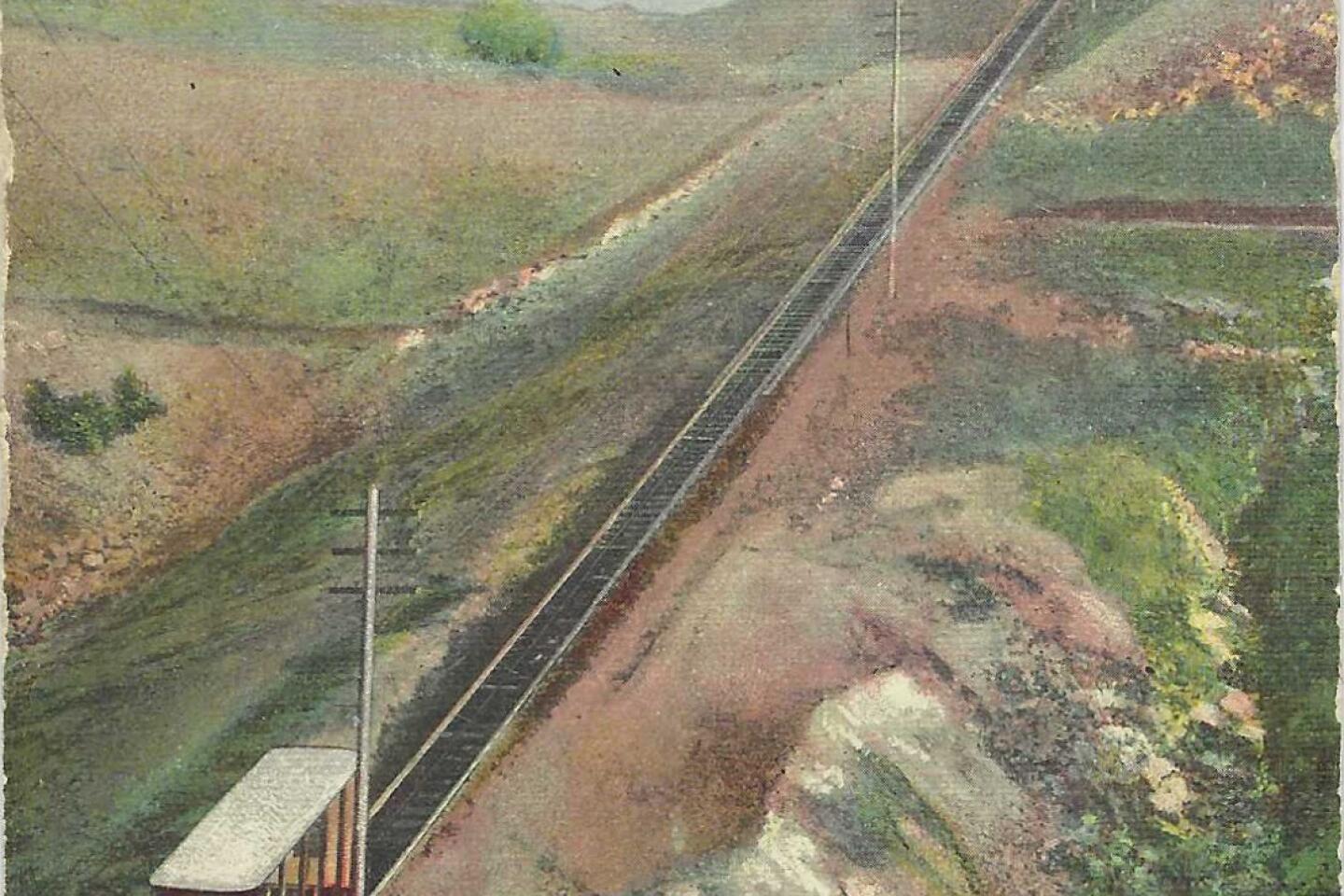

In 1908, a real estate developer named Robert Marsh liked the looks of Mt. Washington, the scrubby hills and canyons above Highland Park, and to entice buyers to become homebuilders, he installed a funicular system like Angels Flight to ascend and descend a thousand feet.

Virginia and Florence, his funicular cars, would stop “every five feet if customers demand it,” Marsh promised, “instead of forcing people to board and alight at the crossings.” At the base of the incline railway was a coffee bar; at the summit, passengers might glimpse Charlie Chaplin in the billiards room of the Mt. Washington Hotel.

Well, it was great while it lasted, which was about a dozen years. In February 1918, a cable broke, and Virginia, or maybe it was Florence, got stuck in mid-ascent. Marsh promised to fix it, and perhaps he did, but in September 1922, the city summoned Marsh to explain — in The Times’ words — “when in the Sam Hill he intends to put his Mt. Washington incline railway into action.” The cars had stopped. The engineer shut down power and disappeared. The cable rusted. “It has been an ex-railway for so long that the cliff-dwellers of Mt. Washington have begged and pleaded with the board to please order Mr. Marsh to pack up his railway tracks, his rusty cable, and dilapidated cars, and take them far, far away.”

And so it came to pass. But into the ’50s and ’60s, traces remained. Times writer Doug Smith grew up in Mt. Washington, and exploring “the hill,” he and a friend turned up pieces of rusted spikes and cables, the bones of the old funicular.

Our most fantastical incline railway wasn’t for commuters, nor for the faint of heart.

In a land of promoters and dreamers, Thaddeus Lowe was a standout visionary, a scientific autodidact who came to California more than 20 years after his service as creator and chief aeronaut of the Union Army balloon corps.

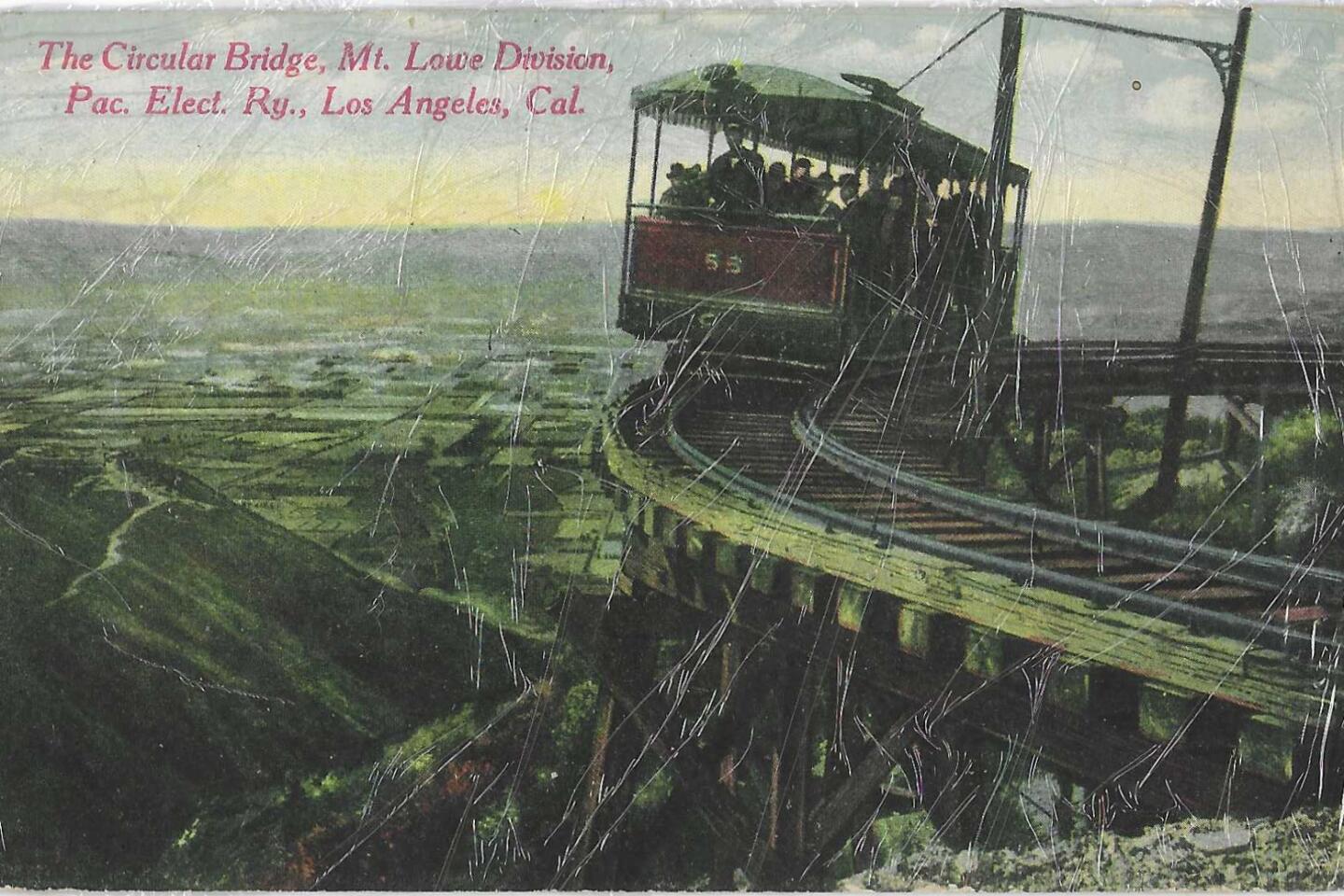

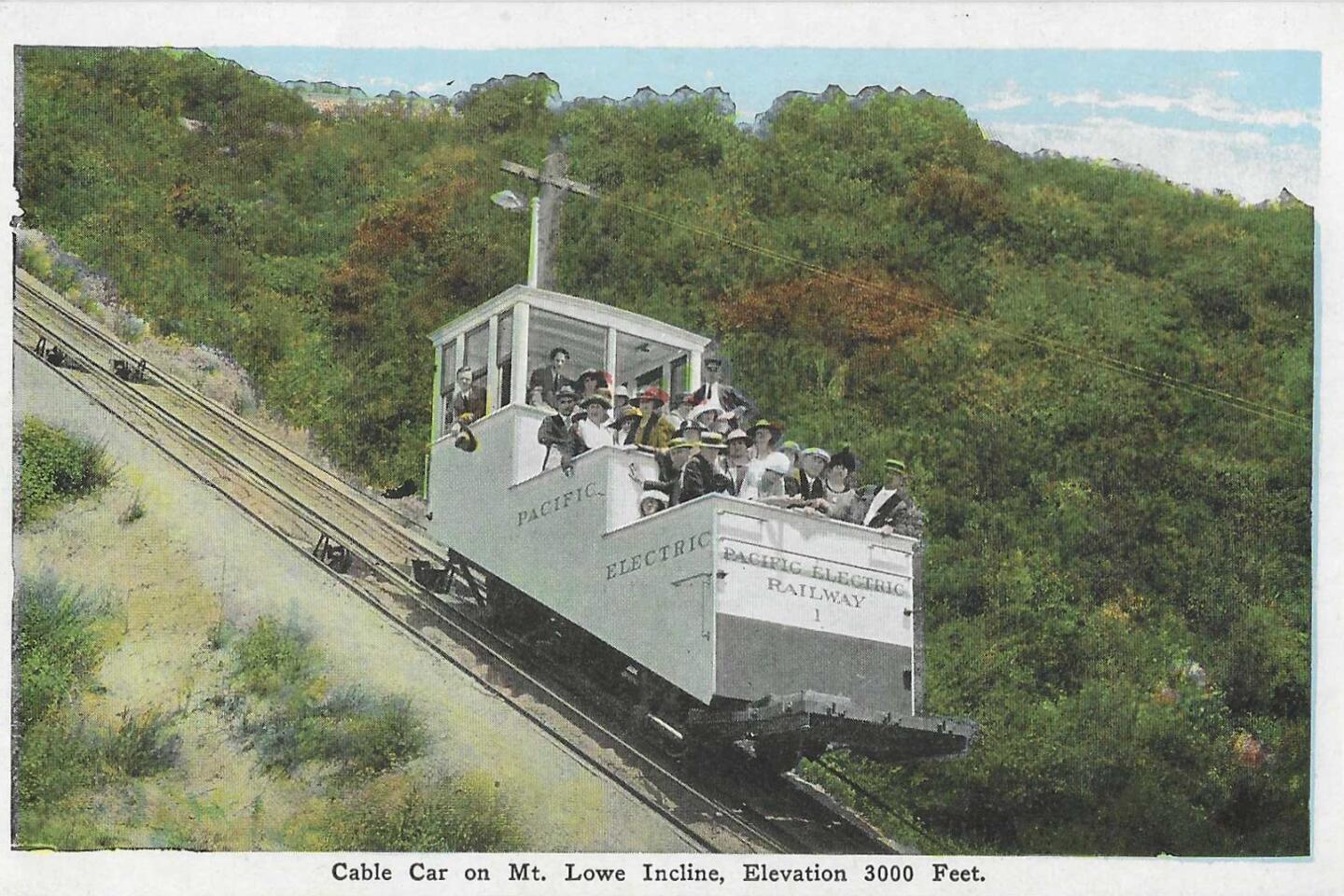

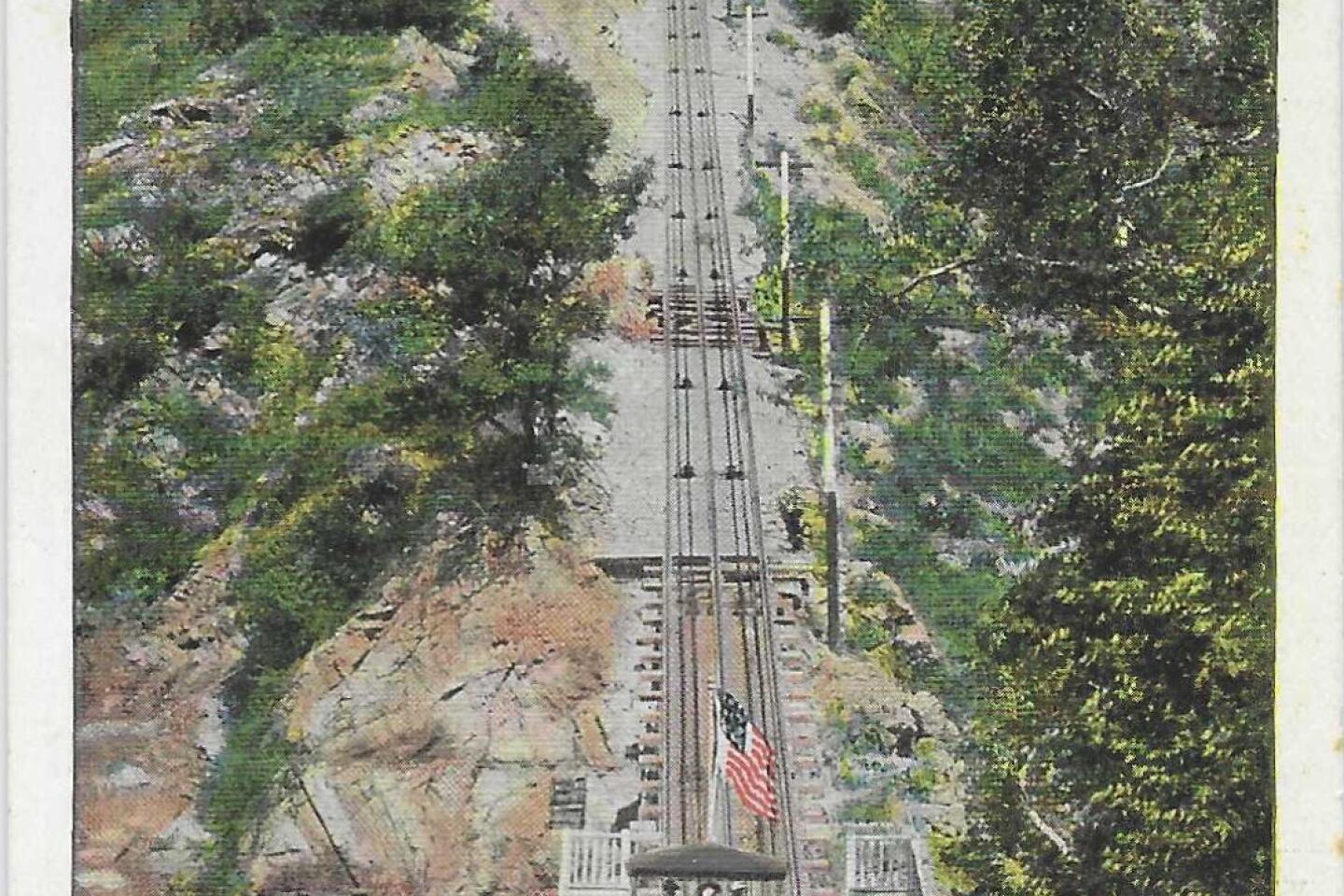

He wanted to give paying customers the same rush that high-flying balloons gave him. His thrill ride was a three-stage, seven-mile trip from Altadena to the summit of Echo Mountain in the San Gabriels.

It opened in 1893 — the same year the Chicago world’s fair was enthralling visitors with the sensational new Ferris wheel. For a daunting $5 fare, passengers took an increasingly daunting trolley ride up from Altadena, transferred to a cable car, then back to a small trolley car, taking so many hairpin turns to the mountaintop that even now, just looking at hundred-year-old postcards of it makes me queasy — Toonerville trolleys edging around a supposed 127 curves in 3½ miles. If visitors’ hearts were still beating, they could enjoy their destination: a mountaintop resort of hotel, tavern, riding trails, dance hall and vistas to the sea.

Now, here is the sad story of creators the world over: Lowe was a better inventor than a businessman, and he soon lost control of his dream project. The relentless Huntington was there to take it over, but even so, the enterprise managed to be both popular and a financial failure.

The aerial railway carried its last rider in 1937, and the fare was a beggarly two Depression-era dollars. By then, buildings had burned down or slid away off the mountain, and in March 1938, the epochal rainfall that disastrously flooded the L.A. River many miles downhill also washed away Lowe’s great enterprise. Pieces of railway were pulled up for scrap during the war. Today, people climb hiking trails that were once the trolley tracks, and the mountain they ascend is now called Mt. Lowe.

“Them: Covenant” on Amazon Prime is a reminder of the all-too-common housing covenants that restricted who could buy homes in certain neighborhoods in Compton, around Southern California and elsewhere. Determined Black people over the decades fought for their rights to live where they pleased.

From its summit it was theoretically possible to see to Catalina Island, which had its own short-lived incline railways. Two were built in 1905: one to a mountaintop amphitheater, the other down to the beach. But — and you saw this coming, didn’t you? — a fire that torched the town of Avalon also scorched the pockets of the family that owned the island. They shut down the funiculars and ended up selling the island in 1919 to William Wrigley Jr., the chewing-gum millionaire and future owner of the Chicago Cubs.

Across the Catalina Channel are L.A.’s beaches, and — elusive as the endangered El Segundo blue butterfly that disports itself there — the ghost of Playa del Rey’s funicular railway.

The Los Angeles Herald reported in 1905 that it was being built, but other accounts say it arose in 1901, to carry people from the beach to a clifftop hotel on “Mt. Ballona.” Some history books will tell you that its counterbalanced cars were named Alphonse and Gaston, after two absurdly courtly Frenchmen, characters in a comic strip. It ran until 1909, and photo evidence of its very existence is slight, to say the least.

Like all those L.A. freeways that got no further than a planner’s map, for every L.A. funicular that was built, two were dreamed up but never came to be:

Griffith Park: In June 1903, buoyed by his Angels Flight’s popularity, Col. Eddy proposed a funicular to Mt. Hollywood in Griffith Park, round trip 50 cents. In exchange, the city wanted 10% of the take, which the colonel said was impossible. In 1908, he was back with the same plan, the round-trip price now two bits, and he was competing with another company for a franchise that never got off the ground, or we would today be able to rumble up the side of Mt. Hollywood, taking selfies all the way.

The Verdugo Incline: For those of you who love coincidence, on the April day in 1912 that the Titanic sank, The Times reported that a former Colorado legislator living in Glendale was proposing a Glendale and Verdugo Mountain Railway, to run from the Casa Verdugo restaurant to the summit of the Verdugos. Like the Titanic, the idea seems to have gone to the bottom.

The East L.A. funicular: In March 1907, a company inquired about donating 15 acres behind the crown of Griffin Avenue in East L.A. for a new teachers’ college. Because the land was on two levels, an incline railway was part of the deal. Class dismissed.

The Monrovia funicular: In 1921, quite late in the elevated railway game, a deal was afoot to build a resort with a sanitarium “for victims of nervous diseases,” and an incline railway to get there and back. Again, DOA.

Each of The Times’ stories ended with the rosy thought that this would surely be beloved by the locals and make great heaps of lucre.

Angelenos can be spotted a mile away in other locales, waiting for the walk sign while locals jaywalk with abandon. What’s that about? And what happens when people do jaywalk here?

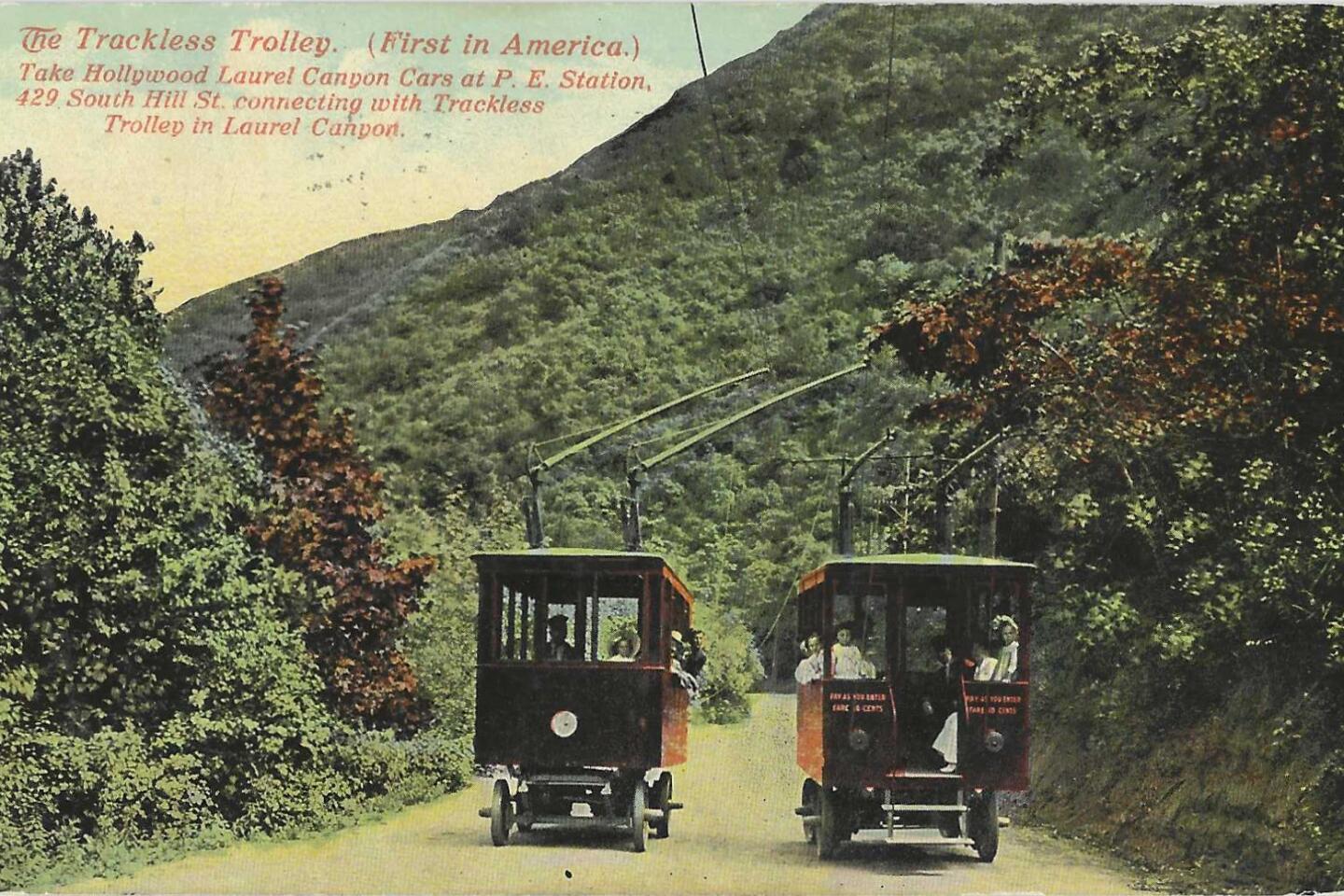

What did work for a time were the “trackless trolleys” of Laurel Canyon, wheeled jitneys operating on power from overhead lines. From September 1910 until 1915, two lively little cars took passengers the mile and a half along Laurel Canyon Boulevard to Lookout Mountain Avenue, giving them a closeup look at lovely acres that could be theirs. In 1915, steam-powered buses took the jitneys’ place, and the thrill, along with the charm, was gone.

What killed off these imaginative experiments? The car in every garage, and the paved roads to entice them. None of L.A.’s funiculars ever inspired a popular song, unlike the counterweight funiculars that started gliding up the side of the Mt. Vesuvius volcano in 1880. “Funiculi, Funicula” has been covered by every Italian tenor for 140 years, by Alvin and the Chipmunks and by the Grateful Dead.

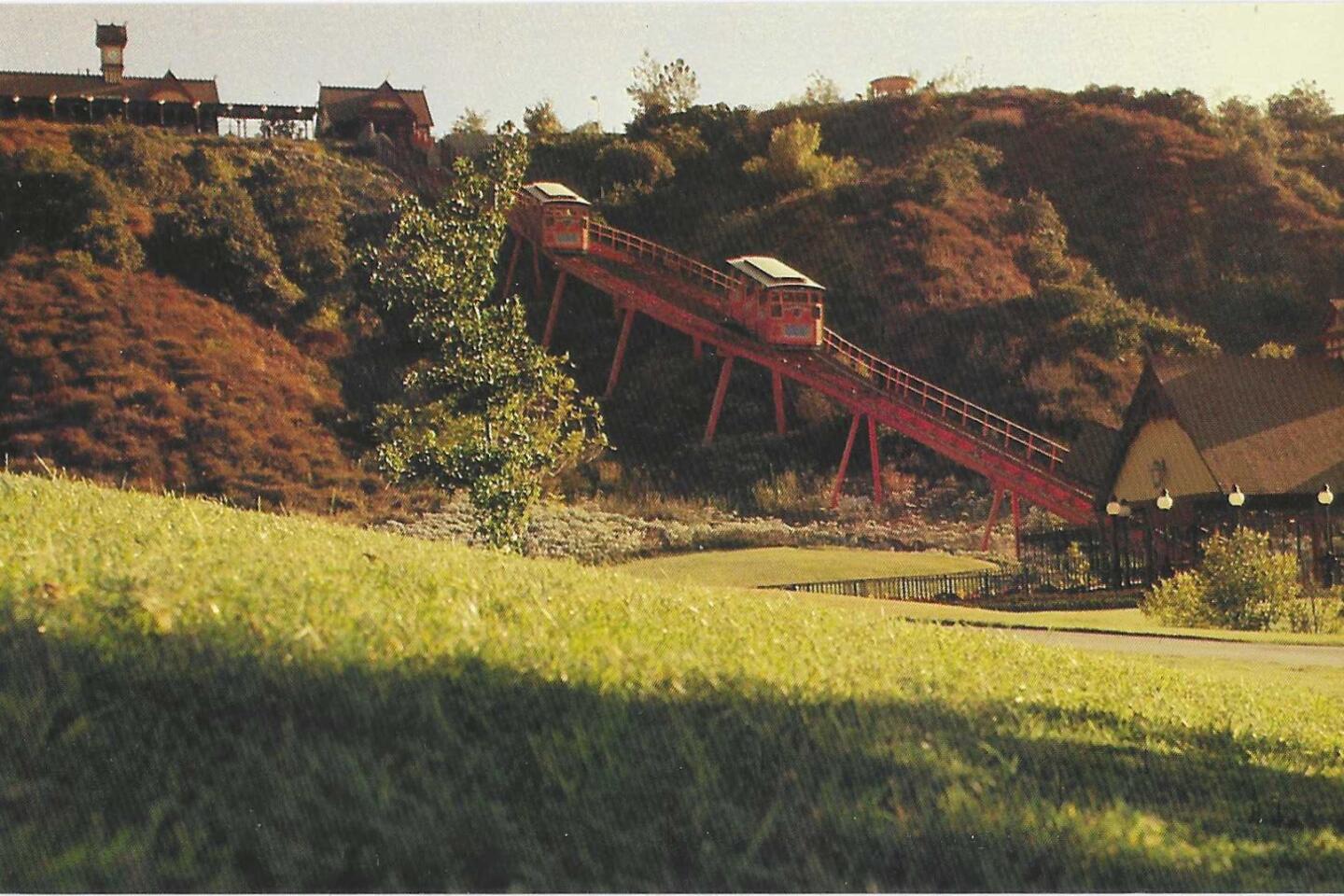

A few private funiculars survive. One, at the golf course in Industry Hills, schleps golfers and gear up to the heights of the last hole. Country singer Kenny Rogers installed an elevated railway on his Malibu estate to take weary players from the tennis court up to an ocean-view veranda. This was coloring outside the legal lines, so Rogers was fined a reputed $2 million. But a few owners later, his incline railway is still there, a selling point for last year’s asking price of $125 million.

As for Angels Flight, its storied history goes on — barely. After the turn of the century, as Bunker Hill slid in status from chic to slummy, Angels Flight appeared in so many noir movies and TV shows that it should have its own SAG card.

In 1969, civic “improvements” shut it down, with the city’s promise that it would reopen. It did — 27 years later. Then its sole fatal accident, in 2001, closed it again, for another nine years. In the first month after it reopened in 2010, it packed 3,000 passengers a day aboard Sinai and Olivet. It was halted briefly the next year for repairs, then once more in 2013 after one car derailed, although no one was hurt.

Finally, at last, nearly 12 decades after it opened, Angels Flight was back in business in 2017 — now with its own trademark registration.

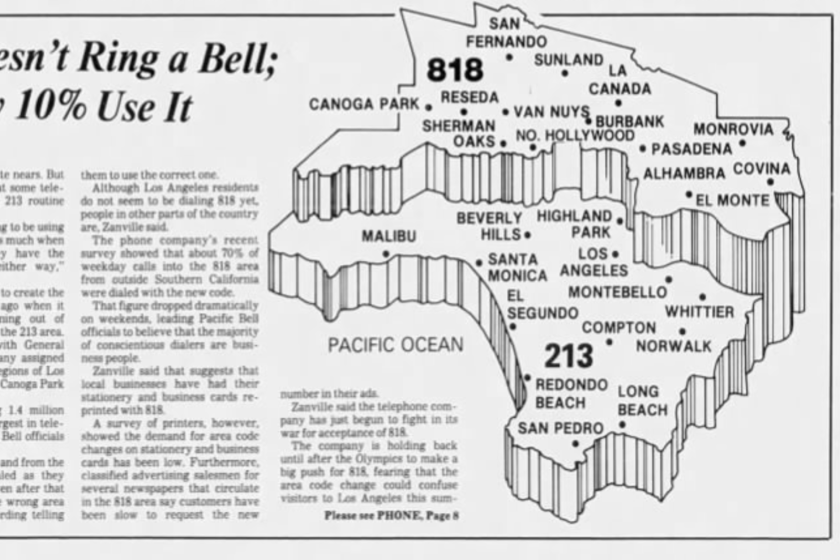

In Southern California, an area code can say a lot about a person. Are you a 310, a 213 or a 323? What does it mean if you have a 562 or an 818?

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.